Corals face an ongoing reduction of oxygen in the sea water. They can survive this condition, but they pay a heavy physiological price that endangers the survival of the corals’ next generations: an impaired ability to capture prey and a growing reliance on energy provided by their symbiotic algae, with a decline in the reproductive processes. These findings emerge from a recent study conducted at the Leon H. Charney School of Marine Sciences at the University of Haifa. “Although corals survive, they pay a penalty. We are concerned that any further environmental changes, especially those affecting the corals’ interaction with their symbiotic algae, will seriously compromise their ability to cope with the declining oxygen levels.” notes Dr. Hagit Kvitt of the University, who led the study.

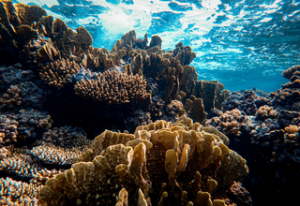

Coral reefs perform numerous important functions for marine ecosystems and human ecology. They provide a habitat for around 25% of all marine organisms and contribute to the biodiversity of the marine system. In addition, coral reefs function as the “rainforests” of the sea: the coral lives in symbiosis with algae that are contained inside its cells and provide about 90% of its energy through the process of photosynthesis.

Global warming is affecting marine life in many ways, one of which is the decrease in seawater oxygen levels. Rising temperatures cause on the one hand a decline in the amount of oxygen dissolved in the ocean and on the other an increase in the metabolism of marine animals, including their need for oxygen. “Consequently, the need for oxygen increases while oxygen levels decrease, which poses a greater threat to the animals than the rise in temperature itself,” the researchers explain. “Previous studies have found that some past mass extinction events were likely caused by a similar combination of rising temperatures and decreasing oxygen levels.”

The current study, published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, was undertaken by Dr. Hagit Kvitt, Dr. Assaf Malik, Prof. Smadar Ben-Tabou de-Leon, Dr. Eli Shemesh, Dr. Maya Lalzar, Prof. Tali Mass, and Prof. Dan Tchernov, researchers at the Charney School of Marine Sciences at the University, together with Dr. Hanna Rosenfeld of the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute in Eilat, and in cooperation with researchers from China. The team sought to monitor the impact of the ongoing decrease in oxygen levels on the physiology and gene expression of a reef-building coral. Previous studies examined the changes in gene expression upon a decrease of oxygen over 12 hours, a relatively short period compared to conditions expected in nature. Studies examining the impact of 11 days of oxygen depletion focused solely on the physiological response and did not examine changes in gene expression. The unique feature of the current study is that it examined both the physiological changes and the changes in gene expression over a longer period – 14 days – when the corals were kept at an oxygen level 90% below the normal level of their natural habitat (a drop from 6 mg/l O2 to 0.3-0.6 mg/l O2). Measurements were taken at three time points – after 12 hours, seven days, and 14 days, at both midday and midnight.

The results of the study show that within the first 12 hours the coral activated processes that helped it cope with the oxygen depletion: it increased its energy production by means that are not dependent on oxygen, it increased the number of mitochondria to improve its utilization of cellular oxygen, and began to increase its nutrient acquisition from the symbiotic algae. After a longer period – between one and two weeks – a decline was seen in processes related to reproduction, in particular those of sperm production, as well as a decline in the production of the stinging mechanism, that functions in prey capture and self defense.

The increased acquisition of nutrients from the symbiotic algae continued at an elevated rate, combined with an increase in the number of algae. “The combination of increased nutrient uptake, on the one hand, and an increase in the number of algae, on the other, increases the coral’s dependence on the algae. As a result, any environmental change that will hamper the symbiosis of the coral with its algae, such as a rise in water temperature, risks compromising the ability of the coral to survive decreasing oxygen levels,” Dr. Kvitt explains.

According to the researchers, the study is very significant in terms of our understanding of the heavy price we will pay for climate change in the future. The combination of decreasing oxygen levels, rising temperatures, and rising acidity in seawater is likely to exert growing pressure on marine life, and particularly on life forms such as corals that are not mobile and cannot escape from areas where sudden changes in seawater occur. “An understanding of which mechanisms are affected by any single form of stress, and which are affected by a combination of several stress agents, will allow us to map the level of damage that will be caused to different organisms. This in turn will help us formulate policies for coping with the climate change we are bringing on ourselves,” the researchers conclude.

27.2.23